1964 NYC SUBWAY PLANNING MAPS (NEW YORK CITY TRANSIT AUTHORITY PLANNING COMMISSION)

$

39.99

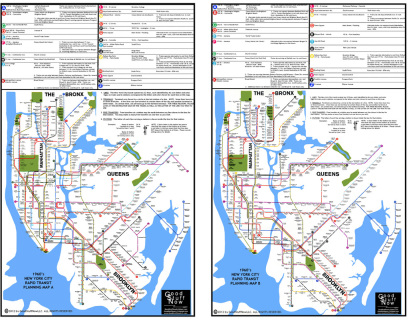

This is PAIR of TWO authentic design reprints based upon the 1964 maps that were designed by Raleigh Dadamo. They measure 18 inches by 24 inches and are ready for framing. These maps were never released to the public and the plan was never put into effect. The special transit commission that came up with these plans was dissolved.

These planning maps were designed by Raleigh Dadamo. One was based upon new construction (Planning Map A) and the other without new construction (Planning Map B). Both maps called for the elimination of numbers and exclusive use of letters on all lines. The routes on these maps were decided by the planning commission. The originals of these maps were attached to the reports by this planning commission.

The New York City Subway System is made up of three former companies that were merged into one system in June 1940. The three former companies were the IRT in 1904, the BRT reorganized in 1923 as the BMT and the IND (Independent) in 1932.

They were operated as three separate DIVISIONS until June of 1948 when the city began installing transfer points between the divisions. Hagstrom (ANDREW HAGSTROM) maps were used for several years (beginning in 1936) and even those maps used only three colors even after the merger the three divisions. These maps used only three colors to identify what lines belonged to what division. The IRT was identified in BLUE, the BMT in yellow and the IND in red.

In 1959 GEORGE SOLOMON designed a new “schematic” type map.

The colors of the three divisions were changed to Black for the IRT, Green for the BMT and RED for the IND.

New York City has many lines merging and diverging from one another. These “divisional” maps simply showed the trunk lines of each division. One could not trace a line or route from one terminal to the other because lines merge and diverge from one another. This lead to the idea of color coding each route.

In 1964 the transit authority sponsored its one and only contest for the design of a new subway map. One of the contestants was Raleigh Dadamo. He entered the contest with an idea for a new concept. His concept was to have a different color for each route. This would make it very easy to trace the path of that route from one terminal to the other.

Raleigh Dadamo approached Andrew Hagstrom (Hagstrom maps) and traced the Hagstrom map, color coding each route. When the contest was concluded those designs that were accepted each of the three finalists received $3000. The Transit Authority called the three finalists and asked those people if they would allow a modification of the rules of the contest so that the Transit Authority could declare a “tie”. Each of the contestants individually agreed.

A tie was declared and each of the contestants received an additional $1000. At a subsequent time as the Transit Authority gave the submissions of the three contestants to a professor at Hofstra College. He turned it over to his class to come up with a final map. The map favored a schematic not geographic style and they came out with a color-coded map where each line had its own color. The problem with this map was the lines were still identified by division and transfer points between the divisions were indicated by usage of red squares where these were interdivisional transfer points were located. It looked like someone had taken a box of strawberries and thrown it against map.

It was an absolute disgrace. Moreover these red boxes interrupted color flow. Because of the interruption of the station boxes Raleigh so I came up with another concept independently and submitted it to the Transit Authority. The transit authority accepted it and came out with the second version that cleaned up the whole map.

However it was still cluttered and at that point William Ronan (first chairman of the MTA) turned the project over to Massimo Vignelli. Massimo took the idea of color coding of each individual line and kept it as a geographic scheme. His first map was printed in 1972.

It was considered a masterpiece of graphic design and simplicity. It eliminated everything geographically was very easy to follow.

In 1979 the Transit Authority abandoned the concept. Some people considered it too confusing and they went back to a geographical map with each route having a color assigned to it according to the TRUNK line it operated on in Manhattan. This meant for example that all routes running on Lexington Avenue would be GREEN, Broadway would be YELLOW, Sixth Avenue would be ORANGE, Eighth Avenue would be BLUE, etc.

The trade-off with this is that you have to identify each route that stops at that station. If each route was color coded a dot could be used to indicate that a train stopped at a particular station.

Massimo Vignelli (born 1931 in Milan, Italy) is a designer who worked in a number of areas ranging from package design, furniture design, public signage and showroom design through Vignelli Associates, which he co-founded with his wife, Lella. He has said, "If you can design one thing, you can design everything," and this is reflected in his broad range of work.

From 1957 to 1960, Vignelli visited America on a fellowship. He returned to New York in 1966 to start the New York branch of a new company, Unimark International, which quickly became, in scope and personnel, one of the largest design firms in the world. The Vignelli firm designed many of the world's most recognizable corporate identities, including that of the iconic signage for the New York City Subway system during this period.

On August 9th 1972 Vingelli released to the public his first “New York City Subway Map”. The former subway map was completely redesigned by Massimo Vignelli. A color scheme for each route was incorporated in this design. Landmarks such as the East River were deliberately distorted in order to pronounce subway lines. One MTA spokesman commented “We tried to make sure that nothing unnecessary distracts the eye from the subway routes. There’s no sense in using a transit map for a geography lesson.”

During this time, a New York City Subway planning committee was established. The goal was to consolidate subway routes into one homogenized system. Discussions took place as to eliminating the IRT’s number lines and using all letters. “Planning Map A” and “Planning Map B” were the results of this planning commission as can be noted with many new lines and service extensions especially in the outer boroughs. This plan was NEVER instituted and died on the drawing table.

PLANNING MAP A:

This concept was based on the building of additional subway lines including a spur to Queens College, York College, Kings Plaza in Brooklyn, the Second Avenue Subway, a shuttle from 14th Street to Houston Street, a huge transfer complex from 60-63 Streets in Manhattan, an L line connecting the South Brooklyn routes, etc.

Much of this never materialized.

PLANNING MAP B:

This concept was based on existing lines and called for relatively no new construction. This was a simple plan to homogenize the entire subway system eliminating the use of numbers to identify lines and only using letters and color coding all the lines.

Interestingly, Phase I of the Chrystie Street project was incorporated into this concept. (North side of the Manhattan Bridge connection to the IND Sixth Avenue Line). Phase II (Williamsburgh Bridge to Sixth Avenue Line) was not incorporated into this plan.

Both plans called for the elimination of the Nassau Loop. (Manhattan Bridge connection to the Nassau Street Line, opened in 1931).

THE FINALIZED CONCEPT

Ultimately the concept of color coded lines was adopted and implemented. The idea of eliminating numbers for the IRT lines was never put into place.

Another plan to use numbers for all lines was not adopted. One reason cited was due to the popularity of the iconic “A” train that has been immortalized in Duke Ellington’s famous song “Take the ‘A’ train”. It was decided that New York City could not eliminate this.

The other major problem with using all letters was eventually there would not be enough letters for all the lines. Both planning map A and planning map B called for the same letter lines going to different terminals at different times of the day!

The color coding of individual lines did not last long. This plan was changed to color coded “trunk lines” in Manhattan. This meant that a line that traveled a particular trunk line would have a similar color. For example, the IRT West Side Lines are RED, IND 8th Avenue Lines are BLUE, IND Sixth Avenue Lines are ORANGE, BMT Broadway Lines are YELLOW, IRT East Side Lines are GREEN, etc.

Check out Raleigh Dadamo on the web

These planning maps were designed by Raleigh Dadamo. One was based upon new construction (Planning Map A) and the other without new construction (Planning Map B). Both maps called for the elimination of numbers and exclusive use of letters on all lines. The routes on these maps were decided by the planning commission. The originals of these maps were attached to the reports by this planning commission.

The New York City Subway System is made up of three former companies that were merged into one system in June 1940. The three former companies were the IRT in 1904, the BRT reorganized in 1923 as the BMT and the IND (Independent) in 1932.

They were operated as three separate DIVISIONS until June of 1948 when the city began installing transfer points between the divisions. Hagstrom (ANDREW HAGSTROM) maps were used for several years (beginning in 1936) and even those maps used only three colors even after the merger the three divisions. These maps used only three colors to identify what lines belonged to what division. The IRT was identified in BLUE, the BMT in yellow and the IND in red.

In 1959 GEORGE SOLOMON designed a new “schematic” type map.

The colors of the three divisions were changed to Black for the IRT, Green for the BMT and RED for the IND.

New York City has many lines merging and diverging from one another. These “divisional” maps simply showed the trunk lines of each division. One could not trace a line or route from one terminal to the other because lines merge and diverge from one another. This lead to the idea of color coding each route.

In 1964 the transit authority sponsored its one and only contest for the design of a new subway map. One of the contestants was Raleigh Dadamo. He entered the contest with an idea for a new concept. His concept was to have a different color for each route. This would make it very easy to trace the path of that route from one terminal to the other.

Raleigh Dadamo approached Andrew Hagstrom (Hagstrom maps) and traced the Hagstrom map, color coding each route. When the contest was concluded those designs that were accepted each of the three finalists received $3000. The Transit Authority called the three finalists and asked those people if they would allow a modification of the rules of the contest so that the Transit Authority could declare a “tie”. Each of the contestants individually agreed.

A tie was declared and each of the contestants received an additional $1000. At a subsequent time as the Transit Authority gave the submissions of the three contestants to a professor at Hofstra College. He turned it over to his class to come up with a final map. The map favored a schematic not geographic style and they came out with a color-coded map where each line had its own color. The problem with this map was the lines were still identified by division and transfer points between the divisions were indicated by usage of red squares where these were interdivisional transfer points were located. It looked like someone had taken a box of strawberries and thrown it against map.

It was an absolute disgrace. Moreover these red boxes interrupted color flow. Because of the interruption of the station boxes Raleigh so I came up with another concept independently and submitted it to the Transit Authority. The transit authority accepted it and came out with the second version that cleaned up the whole map.

However it was still cluttered and at that point William Ronan (first chairman of the MTA) turned the project over to Massimo Vignelli. Massimo took the idea of color coding of each individual line and kept it as a geographic scheme. His first map was printed in 1972.

It was considered a masterpiece of graphic design and simplicity. It eliminated everything geographically was very easy to follow.

In 1979 the Transit Authority abandoned the concept. Some people considered it too confusing and they went back to a geographical map with each route having a color assigned to it according to the TRUNK line it operated on in Manhattan. This meant for example that all routes running on Lexington Avenue would be GREEN, Broadway would be YELLOW, Sixth Avenue would be ORANGE, Eighth Avenue would be BLUE, etc.

The trade-off with this is that you have to identify each route that stops at that station. If each route was color coded a dot could be used to indicate that a train stopped at a particular station.

Massimo Vignelli (born 1931 in Milan, Italy) is a designer who worked in a number of areas ranging from package design, furniture design, public signage and showroom design through Vignelli Associates, which he co-founded with his wife, Lella. He has said, "If you can design one thing, you can design everything," and this is reflected in his broad range of work.

From 1957 to 1960, Vignelli visited America on a fellowship. He returned to New York in 1966 to start the New York branch of a new company, Unimark International, which quickly became, in scope and personnel, one of the largest design firms in the world. The Vignelli firm designed many of the world's most recognizable corporate identities, including that of the iconic signage for the New York City Subway system during this period.

On August 9th 1972 Vingelli released to the public his first “New York City Subway Map”. The former subway map was completely redesigned by Massimo Vignelli. A color scheme for each route was incorporated in this design. Landmarks such as the East River were deliberately distorted in order to pronounce subway lines. One MTA spokesman commented “We tried to make sure that nothing unnecessary distracts the eye from the subway routes. There’s no sense in using a transit map for a geography lesson.”

During this time, a New York City Subway planning committee was established. The goal was to consolidate subway routes into one homogenized system. Discussions took place as to eliminating the IRT’s number lines and using all letters. “Planning Map A” and “Planning Map B” were the results of this planning commission as can be noted with many new lines and service extensions especially in the outer boroughs. This plan was NEVER instituted and died on the drawing table.

PLANNING MAP A:

This concept was based on the building of additional subway lines including a spur to Queens College, York College, Kings Plaza in Brooklyn, the Second Avenue Subway, a shuttle from 14th Street to Houston Street, a huge transfer complex from 60-63 Streets in Manhattan, an L line connecting the South Brooklyn routes, etc.

Much of this never materialized.

PLANNING MAP B:

This concept was based on existing lines and called for relatively no new construction. This was a simple plan to homogenize the entire subway system eliminating the use of numbers to identify lines and only using letters and color coding all the lines.

Interestingly, Phase I of the Chrystie Street project was incorporated into this concept. (North side of the Manhattan Bridge connection to the IND Sixth Avenue Line). Phase II (Williamsburgh Bridge to Sixth Avenue Line) was not incorporated into this plan.

Both plans called for the elimination of the Nassau Loop. (Manhattan Bridge connection to the Nassau Street Line, opened in 1931).

THE FINALIZED CONCEPT

Ultimately the concept of color coded lines was adopted and implemented. The idea of eliminating numbers for the IRT lines was never put into place.

Another plan to use numbers for all lines was not adopted. One reason cited was due to the popularity of the iconic “A” train that has been immortalized in Duke Ellington’s famous song “Take the ‘A’ train”. It was decided that New York City could not eliminate this.

The other major problem with using all letters was eventually there would not be enough letters for all the lines. Both planning map A and planning map B called for the same letter lines going to different terminals at different times of the day!

The color coding of individual lines did not last long. This plan was changed to color coded “trunk lines” in Manhattan. This meant that a line that traveled a particular trunk line would have a similar color. For example, the IRT West Side Lines are RED, IND 8th Avenue Lines are BLUE, IND Sixth Avenue Lines are ORANGE, BMT Broadway Lines are YELLOW, IRT East Side Lines are GREEN, etc.

Check out Raleigh Dadamo on the web